Overview of Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICDs)

Overview of Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICDs)

What is a permanent pacemaker?

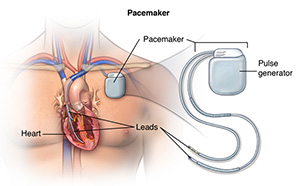

A permanent pacemaker is a small device implanted in the chest to send electrical signals to start or regulate a slow heartbeat. It's most often placed in the chest area just under the collarbone. A pacemaker may be used if the heart's natural pacemaker (the SA node) is not working properly causing a slow heart rate or rhythm, or if the electrical pathways are blocked.

Another specialized type of pacemaker, called a biventricular pacemaker, is used for ventricles that don't contract at the same time. This can worsen heart failure. A biventricular pacemaker paces both ventricles at the same time, increasing the amount of blood pumped by the heart. This type of treatment is called cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT).

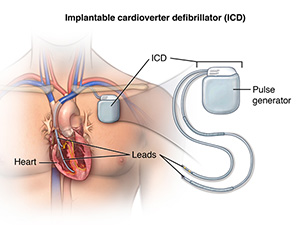

What is an implantable converter defibrillator (ICD)?

An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) looks similar to a pacemaker, though slightly larger. It works very much like a pacemaker. However, the ICD can send a low-energy shock that resets an abnormal heartbeat back to a normal. It can also send a high-energy shock if an arrhythmia becomes so severe that the heart can't pump at all.

Many devices combine a pacemaker and ICD in one unit for people who need both functions. After the shock is delivered, a "back-up" pacing mode is available if needed for a short while.

The ICD has another type of treatment for certain fast rhythms called anti-tachycardia pacing (ATP). This is a fast-pacing impulse sent to correct the rhythm. This can be used instead of shocking the heart in some cases.

What is the reason for getting a pacemaker or an ICD?

Pacemakers are most often used when your heart beats too slowly. ICDs are advised if you are at risk for potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmias. There may be other reasons for your healthcare provider to advise placement of a pacemaker or ICD.

When your heart's natural pacemaker or electrical circuit malfunctions, the signals sent out may become erratic: either too slow, too fast, or too irregular (arrhythmia).

Arrhythmias can cause problems with contractions of the heart chambers by:

Not allowing your heart chambers to fill with enough blood because the heart pumps too fast.

Not allowing enough blood to be pumped out to your body because your heart pumps too slowly or too irregularly.

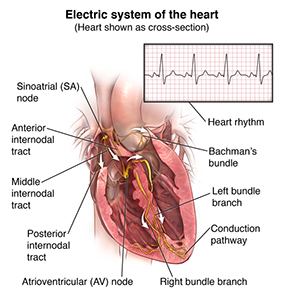

How does the heart beat?

The heart is, in the simplest terms, a pump made up of muscle tissue. The heart's pumping action is regulated by an electrical conduction system that coordinates the contraction of the filling and pumping chambers of the heart.

In an adult, the sinus node generates a steady electrical stimulus. The right and left atria (the two upper chambers of the heart) are stimulated first and contract a short period of time before the right and left ventricles (the two lower chambers of the heart). The electrical impulse travels from the sinus node through the atria to the atrioventricular node (also called AV node), where impulses are slowed down for a very short period, then continue down the conduction pathway via the bundle of His into the ventricles. The bundle of His divides into right and left pathways, called bundle branches, to provide electrical stimulation to the right and left ventricles.

At rest, the heart normally contracts about 60 to 100 times a minute, depending on your age and physical condition. Each contraction of the ventricles is one heartbeat. The atria contract a fraction of a second before the ventricles so their blood empties into the ventricles before the ventricles contract.

Under some abnormal conditions, certain heart tissue is capable of starting a heartbeat, or becoming the pacemaker. An arrhythmia (abnormal heartbeat) occurs when:

The heart's natural pacemaker develops an abnormal rate or rhythm

The normal conduction pathway is interrupted

Another part of the heart takes over as pacemaker

In any of these situations, the body may not get enough blood because the heart cannot pump well. The effects on your body are often the same, however, whether the heartbeat is too fast, too slow, or too irregular. Some symptoms of arrhythmias include:

Weakness

Fatigue

Palpitations

Low blood pressure

Dizziness

Fainting

Shortness of breath

The symptoms of arrhythmias may look like other medical conditions. See your healthcare provider for a diagnosis.

What are the components of a permanent pacemaker/ICD?

A permanent pacemaker or ICD has 3 main components:

A pulse generator with a sealed lithium battery. The pulse generator produces the electrical signals that make the heart beat. Most pulse generators can also receive and respond to signals that are sent by the heart itself.

One or more wires (also called leads). Leads are insulated flexible wires that conduct electrical signals between the heart and the pulse generator. One end of the lead is attached to the pulse generator and the electrode end of the lead is positioned in the heart. In the case of a biventricular pacemaker, leads are placed on both ventricles.

Electrodes, which are found on each lead.

Pacemakers can "sense" when the heart's natural rate falls below the rate that has been programmed into the pacemaker.

Pacemakers that pace either the right atrium or the right ventricle are called "single-chamber" pacemakers. Pacemakers that pace both the right atrium and right ventricle of the heart and require two pacing leads are called "dual-chamber" pacemakers. Pacemakers that pace the right atrium and right and left ventricles are called "biventricular" pacemakers.

How is a pacemaker/ICD implanted?

Your doctor will insert the pacemaker or ICD in the cardiac catheterization, or the electrophysiology lab. You are awake during the procedure, although your doctor will provide local anesthesia over the incision site. He or she will also sedate you to help you relax during the procedure. You may need to spend the night in the hospital so that your doctor can make sure the device is working properly.

Shown here is a chest X-ray. The large, white space in the middle is the heart. The dark spaces on either side are the lungs. The small object in the upper right corner is an implanted pacemaker.

Your doctor will make a small incision just under the collarbone (clavicle). He or she will insert the pacemaker/ICD lead(s) into the heart through a blood vessel that runs under the collarbone. Once the lead is in place, your doctor can test it to make sure it is in the right place and is working. He or she then attaches the lead to the generator (battery), which is placed just under the skin through the incision made earlier. Your doctor will close the incision with stitches, stapes, or a medical adhesive (glue) and apply a dressing. Once the procedure has been completed, you will go through a recovery period or several hours.

There are certain instructions related to having an implanted permanent pacemaker or ICD. For example, after you get your pacemaker or ICD, you will get an ID card from the manufacturer that includes information about your specific model of pacemaker and the serial number as well as how the device works. You should carry this card with you at all times so that the information is always available to any healthcare professional who may have reason to examine or treat you.

After you have a pacemaker or an ICD implanted make sure you ask and understand the instructions from your healthcare provider regarding:

Activity restrictions

Driving

Medicines you should be taking

Any precautions that should be observed with your device

How often you should have follow up appointments

How your device will be monitored

Signs and symptoms you should report to your healthcare provider after the procedure

Updated:

March 21, 2017

Sources:

Minor wound repair with tissue adhesives, Up To Date, Part 6: Electrical Therapies: Automated External Defibrillators, Defibrillation Cardioversion, and Pacing. Link, M. Circulation. 2010, is. 122, ed. 3, s706-19.

Reviewed By:

Kang, Steven, MD,Snyder, Mandy, APRN