Retinitis pigmentosa (RP)

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP)

Natural Standard Monograph, Copyright © 2013 (www.naturalstandard.com). Commercial distribution prohibited. This monograph is intended for informational purposes only, and should not be interpreted as specific medical advice. You should consult with a qualified healthcare provider before making decisions about therapies and/or health conditions.

Related Terms

Alport syndrome, Bassen-Kornzweig disease, blindness, central vision, eye disease, eye disorder, Kearn-Sayre syndrome, Kornzweig disease, night blindness, peripheral vision, pigmentary maculopathy, pigmentary retinopathy, Refsum disease, RP, subcapsular cataracts, Waardenburg syndrome, vitamin A.

Background

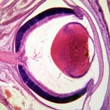

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a group of eye diseases that affect the retina. The retina, which is located at the back of the eye, sends visual images to the brain where they are perceived. The cells in the retina that receive the visual images are called photoreceptors. There are two types of photoreceptors: rods (which are responsible for vision in low light) and cones (which are responsible for color vision and detail in high light).

In RP, the photoreceptors progressively lose function. Side vision, called peripheral vision, slowly worsens over time. Night vision is also affected. Central vision typically declines in the advanced stages of the disease.

Most cases of retinitis pigmentosa are inherited. However, some people develop the disease even if they have no family history. Others may develop the condition as part of another disorder, such as Kornzweig disease, Kearn-Sayre syndrome, Waardenburg syndrome, Alport syndrome, or Refsum disease.

Signs of RP can usually be detected during a routine eye exam when the patient is around 10 years old. However, symptoms usually do not develop until adolescence.

Worldwide, RP is thought to affect roughly one out of 5,000 people.

Although the disease worsens over time, most patients retain at least partial vision, and complete blindness is rare. There is currently no known cure or effective treatment for retinitis pigmentosa, but there are some possible ways to manage the condition.

Risk Factors

Having a family history of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) increases the risk of developing the disorder. However, some people with RP have no family history of the disorder.

Causes

Inheritance: Several different inherited retinal problems can cause retinitis pigmentosa (RP). In most cases, the disorder is caused by a recessive gene. This means that an abnormal gene must be inherited from both parents.

Some cases have also been linked to genetic mutations on the X chromosome.

Other cases are caused by a dominant gene, which means that people develop the disorder if they inherit the mutated gene from just one parent. For example, an estimated 30% of autosomal dominant cases occur when there is a mutation in the gene that codes for rhodopsin, a pigment in the retina that is needed for vision. When the gene is mutated, rhodopsin does not form properly, and photoreceptor cells die.

Currently, genetic testing is available for several genetic mutations, including RLBP1, RP1, RHO, RDS, PRPF8, PRPF3, CRB1, ABCA4, and RPE65.

Random occurrence: Some patients have no family history of the disease. In such cases, the genetic mutation may occur randomly during the development of the egg, sperm, or embryo.

Other syndromes: Other cases may occur as part of other genetic disorders, such as Bassen-Kornzweig disease, Kearns-Sayre syndrome, Waardenburg syndrome, Alport syndrome, or Refsum disease.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) vary among patients. The speed at which the disease progresses also varies.

The first sign of the disease is typically poor night vision or difficulty seeing in dim light. This is generally followed by limited side vision (peripheral vision) and difficulty seeing detailed images. Over time, the disorder may cause tunnel vision, which occurs when the outer edges of vision are dark, so that only objects directly in front of the eye can be seen.

When patients are exposed to bright light or sunlight, they often experience a glare that makes it difficult to see.

Central vision usually starts to deteriorate in the later stages of the disease. Symptoms of central vision loss include difficulty reading or seeing detailed images.

Some people with RP may eventually go blind, although most people are able to maintain some vision throughout their lives.

Diagnosis

Eye examination: An ophthalmologist (eye doctor) can diagnose retinitis pigmentosa (RP). Usually, the doctor uses a special instrument, called an ophthalmoscope, to view the inside of the eye, where the retina is located. If the patient is healthy, the doctor will see an area called the fundus that is orange to red in color. However, if the patient has RP, the fundus will have brown or black spots.

If RP is suspected, an ophthalmologist may confirm a diagnosis by performing an electroretinogram (ERG). This test measures the function of the retina. During the test, different-colored lights are flashed into the eyes as the patient looks at a large reflective globe. An electrode is placed on the eye, and a wire transmits a record of the eye's retinal activity. People with RP have reduced electrical activity in the retina, which indicates that the photoreceptors are not functioning properly.

Visual tests can also be performed to determine the severity of vision loss.

Genetic testing: Many different genetic mutations are known to cause retinitis pigmentosa. Currently, genetic testing is available for several genetic mutations, including RLBP1, RP1, RHO, RDS, PRPF8, PRPF3, CRB1, ABCA4, and RPE65.

Complications

Blindness: Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) causes vision loss that worsens over time. Some people may eventually become blind, although this is rare.

Cataracts: Patients with RP often develop a type of cataract called subcapsular cataracts. When this occurs, the lens becomes cloudy and vision is impaired. Eyeglasses may improve symptoms when cataracts first develop. Later on, surgery may be needed to restore vision.

Retinal detachment: Some patients may experience retinal detachment, which occurs when the retina separates from its attachments to the back of the eyeball. Without prompt treatment, retinal detachment may lead to permanent vision loss.

Interference with daily activities: RP may eventually interfere with daily activities. It may become difficult to drive, especially at night. Individuals are required to pass an eye test before obtaining a new license or renewing an existing license. Some people who have poor night vision may require restrictive driver's licenses that only permit them to drive during the day.

Treatment

General: Currently, there is no known effective treatment for retinitis pigmentosa (RP). However, there are some possible ways to manage the condition.

Special glasses: Many patients experience glare when they are exposed to bright lights. A light amber filter can be added to general eyeglasses to help improve tolerance of bright lights.

Vitamin A: Some research suggests that high doses of vitamin A (about 15,000 international units) may help slow the progression of the disease in some people. However, more research is needed to determine if this is effective. The normal recommended amount for adults is 900 micrograms for men and 700 micrograms for women. Based on recent findings, vitamin A in the palmitate form has been recommended in patients with RP.

Vitamin A toxicity can occur if taken at high dosages. Excessive doses may cause nausea, vomiting, headache, blurred vision, dizziness, liver problems, and clumsiness. It may also increase a person's risk of developing osteoporosis. Vitamin A appears safe in pregnant women if taken at recommended doses. However, excessive doses have been reported to increase the risks of some birth defects. Therefore, Vitamin A supplementation above the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) is not recommended during pregnancy. Use cautiously if breastfeeding because the benefits or dangers to nursing infants are not clearly established. Avoid if allergic to vitamin A. Use cautiously with liver disease or alcoholism. Smokers who consume alcohol and beta-carotene may be at an increased risk for lung cancer or heart disease.

DHA: DHA is an omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid and an antioxidant. Some studies suggest that DHA may help treat RP, while others do not support this therapy. More research is needed to determine if DHA is a safe and effective treatment for this condition.

Calcium channel blockers: Heart medications called calcium channel blockers, such as diltiazem (Cardizem®), have been suggested as a possible treatment for RP. According to some animal studies, calcium channel blockers may reduce the degeneration of the retina. However, not all studies have shown positive effects. Therefore, calcium channel blockers cannot be recommended until more research is performed.

Gene therapy: Gene therapy is currently being studied as a possible treatment for RP. This type of experimental therapy involves replacing or deactivating mutated genes that are causing disorders. Other gene therapy techniques involve inserting a new gene to help the body fight a specific disease. A drug called ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) has been shown to slow the degeneration of photoreceptor cells, although exactly how it works remains unknown. Early research shows that CNTF gene therapy may help stabilize (but not necessarily restore) vision in mice with RP. Gene therapy is experimental and is currently only available in clinical trials.

Integrative Therapies

Good scientific evidence:

Vitamin A: Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin that is derived from two sources, retinoids and carotenoids. Retinoids are found in animal sources (e.g., liver, kidney, eggs, and dairy products). Carotenoids are found in plants, such as dark or yellow vegetables and carrots. Based on recent findings, a common type of vitamin A supplement called vitamin A palmitate, or retinyl palmitate (Aquasol A®, Palmitate A®), has been recommended in patients with retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

Vitamin A toxicity can occur if taken at high dosages. Excessive doses may cause nausea, vomiting, headache, blurred vision, dizziness, liver problems, and clumsiness. It may also increase a person's risk of developing osteoporosis. Vitamin A appears safe in pregnant women if taken at recommended doses. However, excessive doses have been reported to increase the risks of some birth defects. Therefore, Vitamin A supplementation above the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) is not recommended during pregnancy. Use cautiously if breastfeeding because the benefits or dangers to nursing infants are not clearly established. Avoid if allergic to vitamin A. Use cautiously with liver disease or alcoholism. Smokers who consume alcohol and beta-carotene may be at an increased risk for lung cancer or heart disease.

Unclear or conflicting scientific evidence:

Omega-3 fatty acids, fish oil, DHA: DHA is an omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid and an antioxidant. Some studies suggest that DHA may help treat RP, while others do not support this therapy. More research is needed to determine if DHA is a safe and effective treatment for this condition.

Omega-3 fatty acids are generally considered safe if taken in doses that do not exceed the RDA. Avoid if allergic to fish, nuts, linolenic acid, or omega-3 fatty acid products that come from fish or nuts. Avoid during active bleeding. Use cautiously with bleeding disorders, diabetes, and low blood pressure, or if taking drugs, herbs, or supplements that treat any such condition. Use cautiously before surgery.

Fair negative scientific evidence:

Vitamin E: Vitamin E exists in eight different forms: alpha, beta, gamma and delta tocopherol; and alpha, beta, gamma, and delta tocotrienol. Alpha-tocopherol is the most active form in humans. Vitamin E supplements should not be taken in patients with RP, as it does not appear to slow visual decline. It may also be associated with more rapid loss of visual acuity, although the validity of this finding has been questioned.

Traditional or theoretical uses lacking sufficient evidence:

Bilberry: Bilberries are fruits related to wild blueberries and huckleberries found in North America. The use of bilberry fruit in traditional European medicine dates back to the 12th Century. Although fresh bilberries are not commonly found in American grocery stores, they are often used to make jams, pies, cobblers, syrups, and alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages. Limited laboratory studies suggest that bilberry may help treat RP. Until studies in humans are done, this is considered an unproven use.

Long-term side effects and the safety of bilberry remain unknown. Avoid if allergic to bilberry, anthocyanosides (components of bilberry), or other plants in the Ericaceae family. Do not consume bilberry leaves. Use cautiously with bleeding disorders or diabetes. Use cautiously if taking anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications, or drugs that alter blood sugar levels. Stop use before surgeries or dental or diagnostic procedures that have bleeding risks. Use cautiously in doses higher than recommended. Avoid if pregnant or breastfeeding due to a lack of safety evidence.

Magnet therapy: Magnet therapy involves applying various types of magnets to the body. Although magnet therapy has been suggested as a possible treatment for RP, studies are currently lacking.

Avoid with implantable medical devices like heart pacemakers, defibrillators, insulin pumps, or hepatic artery infusion pumps. Avoid with myasthenia gravis or bleeding disorders. Avoid if pregnant or breastfeeding. Magnet therapy is not advised as the sole treatment for potentially serious medical conditions, and it should not delay diagnosis or treatment with more proven methods. Patients are advised to discuss magnet therapy with a qualified healthcare provider before starting treatment.

Ozone therapy: Ozone molecules are composed of three oxygen atoms (O3). There are a number of techniques used to treat people with ozone. Ozone may be mixed with water and then taken by mouth, injected, or introduced into a body cavity such as the vagina, rectum, colon, or ear. Although ozone therapy has been proposed as a possible treatment for RP, studies are currently lacking in this area. Therefore, it remains unknown if this is a safe and effective treatment.

A type of ozone therapy, called autohemotherapy, has been associated with transmission of viral hepatitis and with a possible case of dangerously lowered blood cell counts. Insufflation of the ear carries a risk of tympanic membrane (''ear drum'') damage, and colon insufflation may increase the risk of bowel rupture. Consult a qualified healthcare professional before undergoing any ozone-related treatment.

Prevention

Many different genetic mutations are known to cause retinitis pigmentosa (RP). Currently, genetic testing is available for several genetic mutations, including RLBP1, RP1, RHO, RDS, PRPF8, PRPF3, CRB1, ABCA4, and RPE65.

Patients with family histories of RP can meet with genetic counselors to learn about the risks of having children with the disorder.

Author Information

This information has been edited and peer-reviewed by contributors to the Natural Standard Research Collaboration (www.naturalstandard.com).

Bibliography

Natural Standard developed the above evidence-based information based on a thorough systematic review of the available scientific articles. For comprehensive information about alternative and complementary therapies on the professional level, go to www.naturalstandard.com. Selected references are listed below.

Bhatti MT. Retinitis pigmentosa, pigmentary retinopathies, and neurologic diseases. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006 Sep;6(5):403-13. View Abstract

Demir MN, Unlü N, Yalniz Z, et al. A case of retinal detachment in retinitis pigmentosa. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007 Jul-Aug;17(4):677-9. View Abstract

Gene Clinics. www.geneclinics.org.

Hamel C. Retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006 Oct 11;1:40. View Abstract

Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006 Nov 18;368(9549):1795-809. View Abstract

Koenekoop RK, Lopez I, den Hollander AI, Genetic testing for retinal dystrophies and dysfunctions: benefits, dilemmas and solutions. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007 Jul;35(5):473-85. View Abstract

National Eye Institute (NEI). www.nei.nih.gov.

Natural Standard: The Authority on Integrative Medicine. www.naturalstandard.com.

Retinitis Pigmentosa International. www.rpinternational.org.

Weiss NJ. Low vision management of retinitis pigmentosa. J Am Optom Assoc. 1991 Jan;62(1):42-52. View Abstract

Copyright © 2013 Natural Standard (www.naturalstandard.com)

The information in this monograph is intended for informational purposes only, and is meant to help users better understand health concerns. Information is based on review of scientific research data, historical practice patterns, and clinical experience. This information should not be interpreted as specific medical advice. Users should consult with a qualified healthcare provider for specific questions regarding therapies, diagnosis and/or health conditions, prior to making therapeutic decisions.

Updated:

March 22, 2017