When Your Child Has Pulmonary Stenosis (PS)

When Your Child Has Pulmonary Stenosis (PS)

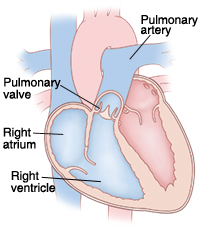

The heart is divided into 4 chambers. The 2 upper chambers are called atria and the 2 lower chambers are called ventricles. The heart contains 4 valves. The valves open and close to keep blood flowing forward through the heart. The pulmonary valve is located between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. It normally has 3 leaflets that open and close to allow blood through. It controls the flow of blood from the heart to the lungs. Pulmonary stenosis (PS) occurs when this valve doesn’t open all the way. It can also occur when the area above or below the valve is too narrow. As a result, blood flow to the lungs is blocked. This condition, left untreated, can lead to certain heart problems over time. But treatment is often available.

Inside view of a normal heart. |

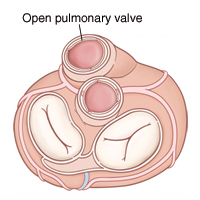

Top view of heart. |

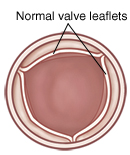

An open normal pulmonary valve (view from above). |

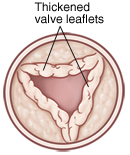

An open pulmonary valve with stenosis. |

Types of pulmonary stenosis

PS can be described as:

Supravalvar, when blockage occurs above the valve (the pulmonary artery may be too narrow).

Valvar, when blockage occurs at the valve (leaflets may be too thick or are stuck together).

Subvalvar, when blockage occurs below the valve (area below the valve may be too narrow).

What causes pulmonary stenosis?

PS is a common congenital heart defect. It occurs in about 10% of people with congenital heart disease. It’s a problem with the structure of the heart that your child was born with. It can be occur by itself, or it can be part of a more complex set of defects. The exact cause is unknown, but most cases seem to occur by chance. Having a family history of heart defects can be a risk factor.

Why is pulmonary stenosis a problem?

PS forces the right ventricle to work harder to pump blood through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery to reach the lungs. This causes the right ventricle to thicken (hypertrophy) and get larger. Over time, the right ventricle can become so overworked that it no longer pumps blood well. This condition is known as heart failure (HF).

Children with valve problems such as PS may be at risk of developing an infection of the heart’s inner lining or valves. This infection is called infective endocarditis.

The thickening of the right ventricle may increase your child's risk for abnormal heart rhythms or heartbeats (arrhythmias).

What are the symptoms of pulmonary stenosis?

Children with mild or moderate PS are usually in normal health and have no symptoms. Severe stenosis can sometimes be diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound. Children with severe or critical PS will usually have symptoms. These can include:

Difficult or rapid breathing

Trouble feeding (in infants)

Poor weight gain (in infants)

Cyanosis (skin, lips, and nails appear blue due to lack of oxygen in the blood)

How is pulmonary stenosis diagnosed?

During a physical exam, the doctor checks for signs of a heart problem such as a heart murmur. This is an extra noise caused when blood doesn’t flow smoothly through the heart. If a heart problem is suspected, your child will be referred to a pediatric cardiologist. This is a doctor who diagnoses and treats heart problems in children. Pulmonary stenosis may happen on its own, or it may be the result of several different problems. To check for PS, the following tests may be done:

Chest X-ray. X-rays are used to take a picture of the heart and lungs.

Low-pulse oximetry. This test detects low oxygen levels before cyanosis develops.

Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). The electrical activity of the heart is recorded.

Echocardiogram (echo). Sound waves (ultrasound) are used to create a pictures of the heart and look for structural defects.

Most children with an isolated PS will not develop symptoms. The murmur may be heard during childhood as part of a well child exam or other visit.

How is pulmonary stenosis treated?

Mild or moderate PS usually requires no treatment. Regular visits with a cardiologist are recommended. This is to make sure that narrowing of the valve doesn’t worsen over time.

Severe or critical PS requires treatment. Your child may be given a medicine temporarily to keep the ductus arteriosus open. This lets blood flow to the pulmonary artery and lungs from the aorta, bypassing the blocked area. The main treatment for PS is a procedure called balloon valvuloplasty. This procedure is described below. Alternatively, open heart surgery to repair or replace the valve is also an option. The cardiologist will tell you more about heart surgery if it’s needed.

Surgery is the treatment of choice for subvalvar and supravalvar PS.

What happens during balloon valvuloplasty?

Balloon valvuloplasty is a procedure done in the heart using a thin, flexible tube called a catheter. It’s done by a cardiologist who has special training to use catheters to treat heart problems (cardiac catheterization). The procedure lasts about 2 to 4 hours. It takes place in a catheterization laboratory or "cath lab." You’ll stay in the waiting room during the procedure.

You’ll be told to keep your child from eating or drinking anything for a certain amount of time before the procedure. Follow these instructions carefully.

Your child is given medicine (sedative or anesthesia). This is to help him or her relax and not feel discomfort or pain during the procedure. A breathing tube may be placed in your child’s trachea (windpipe). Special equipment monitors your child’s heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen levels. The catheter insertion site (the groin) is cleaned and numbed. Then the catheter is inserted into a blood vessel in the groin. With the help of live X-rays, the catheter is advanced up through this blood vessel into the heart. Contrast dye is usually injected through the catheter. The dye allows the inside of the heart to be seen on X-rays. A small balloon at the end of the catheter is inflated one or more times within the pulmonary valve. This forces the valve leaflets to open. The catheter and balloon are then removed.

After the procedure, your child is taken to a recovery room. You can stay with your child during much of this time. It may take 1 to 4 hours for sedative medicines to wear off. Pressure is applied to the catheter insertion site to limit bleeding. The doctor or nurse will tell you how long your child needs to lie down and keep the insertion site still. Your child is cared for and monitored until he or she can leave the hospital. An overnight hospital stay is usually required.

What are the complications of balloon valvuloplasty?

Risks and possible complications of balloon valvuloplasty include:

Reaction to contrast dye

Reaction to sedative or anesthesia

Pain, swelling, redness, bleeding, or drainage at the catheter insertion site

Leakage of blood through the pulmonary valve back into the right ventricle

Abnormal heart rhythm

The need for further treatment to repair or replace the valve

Injury to the heart or a blood vessel

In general, complications after balloon valvuloplasty are extremely rare.

When to seek medical advice

Call your healthcare provider right away if any of these occur:

Increased pain, swelling, redness, bleeding, or drainage at the catheter insertion site

Fever

An irregular heartbeat

Breathing difficulty, shortness of breath, or chest pain

Lightheadedness or fainting

Arm or leg turns blue or feels cold

What are the long-term concerns?

All treatment options for PS are done to relieve symptoms. This means that the pulmonary valve is not repaired and will always be somewhat abnormal. Further problems with the valve may occur again in the future.

After treatment, most children with PS can be as active as other children.

Regular follow-up visits with a cardiologist are needed. This is to make sure the valve doesn’t become blocked again or have too much leakage. The frequency of these visits may decrease as your child grows older.

Updated:

August 16, 2018

Sources:

Pulmonic Stenosis in neonates, infants, and children, Up To Date

Reviewed By:

Ayden, Scott, MD,Bass, Pat F. III, MD, MPH,Image reviewed by StayWell medical illustration team.