Laryngeal Cancer: Surgery

Laryngeal Cancer: Surgery

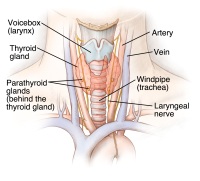

Laryngeal cancer is commonly treated with surgery to remove the cancer. All or part of the larynx, or voice box, may be removed. This type of surgery is called laryngectomy. The type of procedure needed depends on where the cancer is in the larynx and how big it is. Laryngectomy is often done along with other treatments, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, to destroy the cancer and help keep it from coming back.

Types of surgery for laryngeal cancer

Depending on the stage and location of the cancer, different surgical procedures may be done. If the cancer has spread, the doctor may also need to remove some of the lymph nodes or muscles in the neck near the larynx. Types of procedures include:

-

Partial laryngectomy. This removes part of the larynx, or voice box.

-

Total laryngectomy. Surgery to remove the entire larynx. This may be the only effective option for advanced laryngeal cancer. A hole is made in the front of the neck so you can breathe. You won’t be able to talk after this surgery.

-

Hemilaryngectomy. Surgery to remove only half or one side of the larynx.

-

Thyroidectomy. Surgery to remove the thyroid gland.

-

Cordectomy. Surgery to remove only some or all of the vocal cords.

-

Vocal cord stripping. This removes the cancer cells from the surface of the vocal cords.

-

Laser surgery. Uses a laser to remove a tumor or defect on the surface of the larynx.

-

Supraglottic laryngectomy. Removes only the top portion of the larynx.

-

Neck dissection. Surgery to remove the lymph nodes in the neck where cancer has spread.

The larynx is part of how we eat, breathe, and talk. Surgery in this area might also affect how you look. There are many ways to treat this cancer with surgery. Be sure you understand what type of surgery is best for you and how your body will work after it.

Risks of laryngeal cancer surgery

All surgery has risks. The risks of laryngeal surgery include:

-

Excess bleeding

-

Bruising

-

Infection

-

Swelling in your mouth or throat, which can make it hard to breathe

Possible long-term or permanent side effects depend on the type of surgery and include:

-

Damage to nerves and other tissues near the cancer that causes numbness

-

Scarring

-

Changes in how you eat

-

Changes in your sense of smell and taste

-

Changes in how you talk or not being able to talk the way you did before

-

Changes in how you breathe

-

Changes in how you look

Talk with your healthcare provider about the side effects you may have and the chances of side effects affecting you after surgery.

Getting ready for your surgery

Your healthcare team will talk with you about the surgery options that are best for you. Make sure to ask about:

-

What type of surgery will be done

-

What will be done during surgery

-

The risks and possible side effects of the surgery

-

If there will be changes in how you talk, breathe, or eat

-

When you can return to your normal activities

-

What you will look like after surgery

After you have discussed all the details with the surgeon, you will sign a consent form. This gives the surgeon permission to do the surgery.

You’ll also meet the anesthesiologist and can ask questions about the anesthesia and how it will affect you. Just before your surgery, an anesthesiologist or a nurse anesthetist will give you the anesthesia medicines so that you fall asleep and don’t feel pain.

What to expect after surgery

After surgery for laryngeal cancer, you may have to adjust to new ways of eating, drinking, speaking, and breathing. The types of changes you have depend on the type of surgery that was done.

Learning to speak

Total laryngectomy takes away your ability to speak using your vocal cords. A therapist called a speech-language pathologist will work with you to help you to speak again. But your voice will sound different. Surgery might also be done later to help you speak again.

If your entire larynx is removed, you'll need to learn to speak in a new way. This will take practice. Before surgery or soon after, the speech-language pathologist may talk with you about your choices for speech. These include:

-

Esophageal speech. For this approach, the speech-language pathologist teaches you how to swallow and then release air like a burp from the walls of your throat. You can learn how to form words from the released air with your lips, tongue, and teeth.

-

Tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP). This surgery is done either when the larynx is removed or as a separate surgery later. The surgeon makes a small hole between your trachea and esophagus, and places a small device in the opening. With practice, you can learn to speak by covering the hole and forcing air through the device. The air makes sound by vibrating the walls of your throat.

-

Electric larynx. An electric larynx is a small battery-powered device. It makes a humming sound like the vocal cords, and you move your lips to form words. Some models are used in the mouth, while other models are placed on the neck.

Breathing changes

The larynx also plays an important role in controlling breathing. When all of the larynx is removed, surgeons need to create a new way of breathing. The surgical team will create a hole in your neck called a tracheostomy. The surgeon will permanently connect your windpipe or trachea, which carries air to the lungs, to this hole in the front of your neck. Breathing, coughing, and sneezing now occur through this hole, called a stoma, rather than through your nose and mouth.

The stoma may be held open with a tube you breathe through. This tube is called a tracheostomy tube, or trach tube. The trach tube stays in place for a few weeks, until the skin around the stoma heals. Some people continue to use the tube all or part of the time. If it is removed, a smaller tracheostomy button, called a stoma button, often replaces the tube. After a while, some people don’t use a tube or a button in the stoma.

After a partial laryngectomy, a short-term tracheostomy may be needed. Then the trach tube is removed from the stoma. Over the next few weeks, the stoma closes. You then breathe and speak in the usual way, although your voice may not sound the same as before.

The stoma must be correctly cared for to prevent problems and complications. Your healthcare team will help you learn how to care for it.

Eating on your own

For a few days after surgery, you won’t be able to eat or drink. At first, you’ll get nutrients through a tube into one of your veins. This is called IV or intravenous feeding.

In a day or so, your digestive tract will return to normal. But you won’t be able to swallow because your throat won’t be healed. You’ll get foods and liquids through a feeding tube that goes through your nose and throat to your stomach. The surgeon places this tube during surgery. It will be taken out when your throat heals. This will allow you to swallow again and take in enough food through your mouth to maintain your weight.

Swallowing may be hard at first, and you may need the help of a nurse or speech-language pathologist to learn how to swallow again. Over time, you will return to a regular diet.

Recovering at home

When you get home, you may get back to light activity. But you should not do any strenuous activity for about 6 weeks. Your healthcare team will tell you what kinds of activities are safe for you while you recover.

If you had surgery to remove lymph nodes in your neck, your shoulder and neck may be weak and become stiff. A physical therapist can help you with special exercises if this happens.

When to call your healthcare provider

Let your healthcare provider know right away if you have any of these problems after surgery:

-

Bleeding

-

Breathing problems

-

Redness, swelling, or fluid leaking from the incision

-

Fever

-

Chills

There may be other things your healthcare provider wants you to watch for. Be sure you know how to reach your provider after office hours and on weekends.

Updated:

June 04, 2019

Reviewed By:

Gersten, Todd, MD,LoCicero, Richard, MD