Learning to Speak Again After Laryngeal Surgery

Learning to Speak Again After Laryngeal Surgery

Laryngeal cancer is cancer of the larynx, or voice box. Treatment may include a full laryngectomy, meaning the larynx is surgically removed. This takes away your ability to speak using the vocal cords.

Modern advances in surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy treatment, however, can often save the larynx or part of it. Keeping the larynx saves the voice, even if its quality is changed. If the cancer is very advanced, though, removing the larynx may still be the best choice.

What is the larynx?

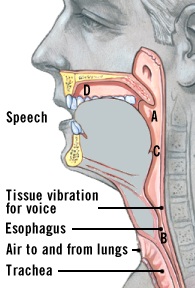

The larynx, also known as the voice box, opens to help you to breathe. When you swallow, it keeps food out of the trachea, which is the windpipe. Air passing through the larynx causes the vocal cords to vibrate, producing sound. With the help of your mouth, teeth, tongue, and lips, that sound becomes your voice.

What happens when the larynx is removed?

When the larynx is removed, the surgeon trims and turns the trachea to create an opening in the front of the neck. This opening, called a stoma, is the new passage for breathing. It bypasses the nose and mouth. During the operation, the surgeon inserts a tracheostomy tube in the stoma to hold it open. A few weeks later, the healthcare provider may replace the tube with a tracheostomy button, commonly called a stoma button. Some people without a larynx leave the trach tube in. Others, after some time, don't use either the tube or the button.

Preparing for surgery

A speech-language pathologist (SLP) will meet with you before your surgery. The SLP will evaluate your speech and explain your communication options after surgery.

SLPs counsel patients before surgery to put them at ease and to let them know that they'll be able to communicate right after surgery.

You need to know that even if only a part of your larynx is removed, your voice won't sound the same as it did before the operation. It will have a lower pitch. Talking to be heard in loud situations may be difficult. You'll need to practice each type of speech, try to relax when speaking, and be patient. Remember, learning how to speak as a child wasn't easy, either. Your sense of smell and taste may also be affected.

After surgery

For a few days after surgery, you won't be allowed to speak. This is because healthcare providers don't want you to move your tongue around and pull apart the sutures. To help you heal, you'll be fed through a feeding tube for a week or so. The type of feeding tube and length of time you'll need it depend on the type of surgery you've had. A humidifier in your hospital room will moisten the air to help keep the stoma from drying out. You may also be taught how to use a suction machine to remove excess mucus.

Speaking again

Before learning to speak again, you can communicate by writing. You might want to bring a laptop computer with you to the hospital so that you can write notes to caregivers and send emails to family and friends.

Speech therapy usually begins before you leave the hospital. Once the healthcare provider gives approval, the SLP will begin speech lessons with you. Learning to talk again may involve things like esophageal speech, an artificial larynx, or a transesophageal puncture (TEP). Each is described below.

Esophageal speech

Esophageal speech is when you take air into your esophagus and let it out. The top of your esophagus then vibrates and produces sound. It's kind of like a belch, but different—the air isn't coming from the stomach. Air is pulled in (inhaled or taken in using the lips or the tongue) right below that vibrating segment, and then it comes out. It's a more controlled way to produce sound. You'll learn how to use your lips, tongue, and teeth to form words from the released air.

Esophageal speech is difficult and takes time to learn—often up to 6 months.

After you leave the hospital, you'll continue to learn esophageal speech with the SLP, probably about once a week. You may also have a home health speech therapist visit a few times a week. Some hospitals offer intensive laryngectomee workshops to teach esophageal speech. Learning to speak this way may be a challenge, but you won't need any apparatus or additional surgery.

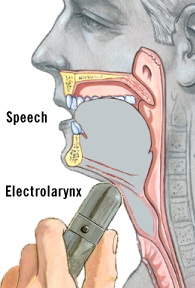

Artificial larynx (AL)

You can learn to use an artificial larynx while you're still in the hospital. With a little practice, you can communicate immediately with an AL and can even use it to speak on the telephone.

There are two types of artificial larynxes—neck type and intraoral:

-

The neck type is placed on your skin on the side of your neck, under your chin, or on your cheek. It may take some experimenting to find the position on your neck or near your mouth that makes the best-sounding voice.

-

The intraoral type of AL is a small tube that goes in your mouth. It's best to use your nondominant hand to hold the AL so that your dominant hand is free to write or shake hands.

Some people stick with the AL as their form of speech because they can communicate right away and don't need another operation to use it.

Although communication is immediate with ALs and the devices are easy to use, some people don't like the mechanical quality of the resulting voice.

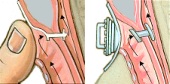

Tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP)

A TEP prosthesis is inserted into a small hole or puncture that the surgeon makes between your windpipe and your esophagus. You may need another operation for this. Some healthcare providers perform a TEP at the same time as the laryngectomy. Usually, you can decide if you want a TEP, or the healthcare provider and the SLP may suggest it if esophageal voice is not working.

To speak with a TEP, you take a deep breath and then cover the stoma so that when you exhale, the air that would normally come out of the stoma is shunted through a little prosthesis (a TEP valve). The air goes through the one-way valve of the prosthesis, then up your esophagus, where muscle vibrations help to produce voice. You can either cover your stoma with your finger when speaking, or you can get a "hands-free" tracheostoma valve. A TEP lets you develop a natural-sounding voice and good sound quality within a few weeks after surgery.

Learn from others

When the larynx is removed, the usual method of producing voice is also lost. It's important to remember that laryngectomees (someone who has had cancer and laryngectomy surgery) can speak again. You just have to learn a new way to speak.

A laryngectomee is sometimes called a "lary." You can find a lary to talk to through laryngectomee clubs, often called "Lost Cord" or "Nu-Voice" clubs. You'll find a list of clubs on the International Association of Laryngectomees website.

Updated:

June 04, 2019

Sources:

A brief review of voice restoration following total laryngectomy. M Kapila. Indian J of Ca. 2011. 48/1 (99-104)., Total laryngectomy - past, present, future. Ceachir O.Maedica (Buchar). 2014. 9/2(210-216).

Reviewed By:

Gersten, Todd, MD,Stump-Sutliff, Kim, RN, MSN, AOCNS